For over two millennia, the grandeur and mystery of ancient Egypt have fascinated people across the globe. This enduring fascination—known as Egyptomania—has surged at key moments in history, notably after Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign in Egypt at the end of the 18th century and again following the 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

The unearthing of Tutankhamun’s burial site ignited a frenzy across Europe and the United States. Art, fashion, literature, and film were suddenly filled with Egyptian motifs and imagery. The early 20th century’s Art Deco movement, for example, borrowed heavily from ancient Egyptian designs, while the so-called “mummy’s curse” surrounding Tut’s tomb inspired a wave of mystery novels and Hollywood horror films. Even today, modern establishments like the Luxor Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas continue to profit from this cultural obsession.

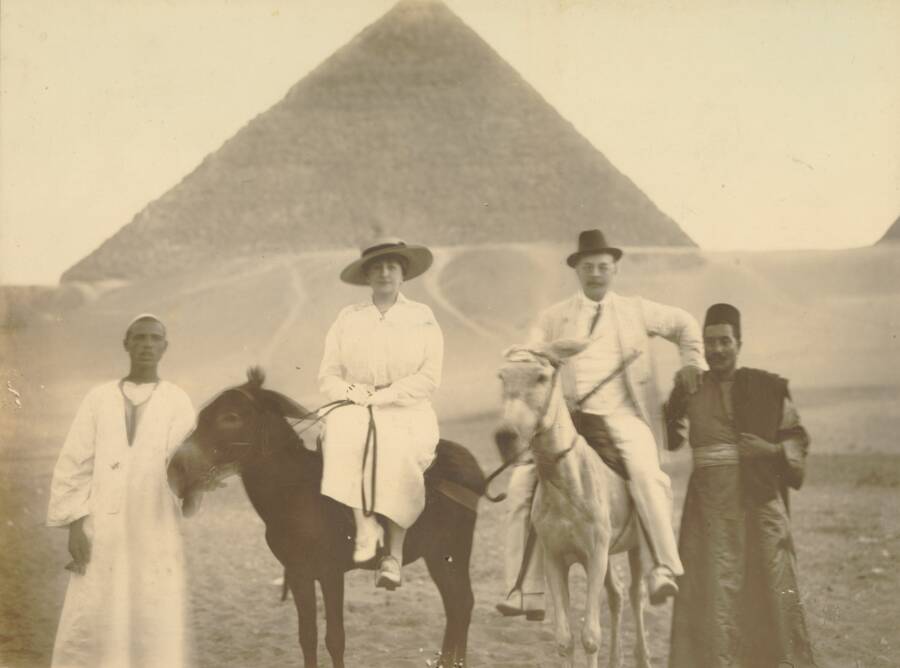

During the 19th and 20th centuries, affluent travelers flocked to iconic sites such as Giza and Luxor to experience the ancient world firsthand. For those who couldn’t make the journey, ancient Egypt came alive through exhibitions, media, and decorative trends that swept Western society.

A Longstanding Fascination: Egypt in the Eyes of Greece and Rome

Though the term Egyptomania is modern, the phenomenon itself dates back thousands of years. The Greeks and Romans were among the earliest to marvel at Egypt’s ancient wonders. Their interactions with Egyptian culture were extensive and often admiring—perhaps most famously embodied by the legendary romance between Cleopatra and Marc Antony.

Yet long before Cleopatra’s dramatic end, Egypt had already captivated the imagination of the classical world. To the Greeks and Romans, Egypt was an ancient land filled with secrets, wisdom, and monumental achievements. As one Egyptian priest is said to have told a visiting Greek: “You Greeks are children.”

To put this in perspective, the New Kingdom—ancient Egypt’s height of power—spanned from approximately 1550 to 1070 B.C.E. In contrast, classical Greece began to emerge around the 8th century B.C.E., and the Roman Republic wouldn’t be established until 509 B.C.E. To these civilizations, Egypt was already the stuff of legends.

Public DomainEuropean tourists in Egypt circa 1925.

Classical era Greeks interacted with the ancient Egyptians often, and historians like Herodotus noted many similarities between Greek and Egyptian deities, suggesting that Egyptian religion likely had a large influence on the Greek pantheon. A similar observation could be made between Egyptian and Greek architecture, particularly when it came to temple design.

Greek scholars, including Pythagoras and Plato, are also believed to have studied in Egypt, where they developed the knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy that they later integrated into Greek thought.

Hundreds of years later, Egyptomania struck Rome. Like the Greeks, the Romans took architectural cues from the Egyptians. However, they took it a step further by importing obelisks and statues straight from Egypt to their cities following the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 B.C.E.

Of course, this fascination did not fade even after the collapse of the Roman Empire. More than 1,000 years later, another wave of Egyptomania swept throughout Europe — thanks to none other than Napoleon Bonaparte.

How Napoleon’s Campaign Led To Egyptomania In Europe

Public DomainThe Battle of the Pyramids (1810) by Antoine-Jean Gros depicts Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in July 1798.

Starting in 1798, Napoleon led a significant military and scientific campaign in Egypt. Aiming to undermine British access to India and expand French influence, Napoleon invaded Egypt with his military forces and more than 150 scientists, engineers, and artists, collectively known as “savants.”

The multidisciplinary team was tasked with studying and documenting Egypt’s antiquities, natural history, and culture, which led to several significant achievements, including the establishment of the Institut d’Égypte in Cairo and a vast publication of the savants’ collective observations known as the Description de l’Égypte.

The most significant outcome of this campaign, however, was the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, an artifact that proved instrumental in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Napoleon’s military campaign was ultimately unsuccessful, but the artifacts that the French brought back from Egypt and the publication of the Description de l’Égypte kickstarted a new wave of Egyptomania across Europe. Egyptian Revival architecture became a popular design choice, often incorporating motifs like sphinxes, obelisks, and pyramidal structures.

Artists and writers also drew inspiration from Egyptian themes, producing works that romanticized and reimagined ancient Egyptian life and mythology. Likewise, Egyptian motifs started appearing commonly in the fashion of the era, with elements like lotus flowers, scarabs, and hieroglyph patterns adorning clothing, jewelry, furniture, and other household items.

Naturally, this new, widespread fascination with Egypt prompted further archaeological explorations and a deeper scholarly interest in Egyptian history as well. This soared to new heights a century later when King Tutankhamun’s tomb was rediscovered in 1922.

Tutmania Of The 1920s And Egyptomania In The United States

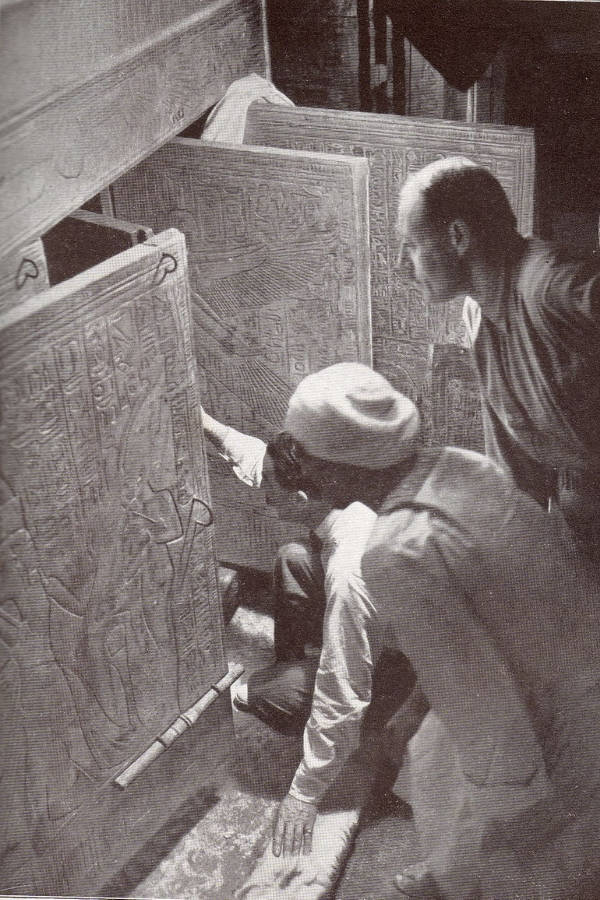

After explorer Howard Carter found the long-lost tomb of King Tutankhamun, a new global phenomenon known as “Tutmania” took the world by storm.

When Carter first came across Tut’s tomb, he wrote in his notebook that it was reminiscent of the “property-room of an opera of a vanished civilization.” The “wonderful things” he found inside included numerous ancient artifacts like King Tut’s sandals, jars full of ancient alcohol, and, of course, the Boy King’s sarcophagus. Over the next 10 years, Carter and his team extracted more than 5,000 artifacts from the royal’s burial place to show off to the world.

Public DomainHoward Carter looking into King Tut’s tomb in 1924.

Carter also spent a lot of time traveling and talking about his work. In particular, he spoke often at both the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts, leading him to be credited with bringing Egyptomania to the United States.

Americans were captivated by Carter’s discovery. It was a media firestorm, and as Carter traveled about with the ancient treasures, the designs and motifs featured on them also came to be incorporated into American fashion and architecture. Egyptian symbols were frequently combined with the Art Deco style, helping to craft the aesthetic of the ’20s.

Like in Europe, the arts also picked up on this trend. Many classic Hollywood films were centered around ancient Egypt well into the 1960s and ’70s — the most famous example being Cleopatra (1963) starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Many of them centered on the legend of the “mummy’s curse” associated with King Tut’s tomb.

Ancient Egyptian influence was pervasive throughout all of American culture in the 1920s. Consumer goods featured Egyptian-inspired designs, and architectural trends incorporated Egyptian motifs. Everywhere you looked, ancient Egypt was looking back.

In one 2003 study, the University of Delaware’s Katherine A. Hunt observed that “through Egyptian imagery, Americans were able to engage issues concerning society in the 1920s: class disparity, faith, shaping one’s identity, definitions of beauty, the role of women in modern society, and color politics in the African-American community.”

Public DomainThe Sphinx of the Fontaine du Palmier in Paris, which was built between 1806 and 1808.

Hunt suggested that the fascination with such an “exotic location” was representative of a “fundamental uncertainty underlying American culture in the twenties.”

In a sense, the American Egyptomania craze of the 1920s was a form of escapism. It allowed people to discuss the issues of the modern day through the lens of ancient history while also providing something permanent to hold on to. The fact that the Sphinx and the pyramids had remained intact for thousands of years offered reassurance that, even though the times were changing, some things would always remain the same.